I Dont Want to Be Feed

While pressuring a child to eat is usually done with the best of intentions, it can have unintended consequences.

Parents are often worried when their child eats very little, does not eat healthy foods like fruits and vegetables, or refuses a meal completely. For some, this worry can be significant, particularly if the child is not gaining weight well, or is losing weight. For others, uneaten meals can be a source of frustration.

Often parents find themselves using pressure, force or coercion to try and get their child to finish their meal.

This can take many forms:

- Pressure - "I want you to eat all of your carrots"

- Coaxing - "Just eat that little, tiny piece there"

- Emotional blackmail - "A good girl would eat their dinner after Mummy worked so hard cooking it"

- Use of rules - "Eat your age; three potatoes because you are three years old"

- Bribery - "If you eat everything on your plate then you can leave the table"

- Punishments - "You can't go and play outside unless you finish your spaghetti"

- Force-feeding - physically putting food into the child's mouth and forcing them to swallow

Using all of these behaviours has the opposite effect to what was intended.

While a child may eat a little more when being coerced, the act of being pressured into eating can lead to the development of negative associations with the food, and ultimately dislike and avoidance. It can also stop children from recognising and responding appropriately to internal signals of hunger and fullness, which can make them more likely to overeat in later life.

Why is it bad to pressure or strongly encourage a child to eat?

Parents' use of pressure to eat often stems from worry and anxiety regarding how or what a child is eating. Parents can become concerned about their child's health and wellbeing (and ultimate survival) if they feel that their child is not eating enough to sustain healthy development. If a child is underweight, parents are more likely to want to encourage eating and may end up using pressure without realising that they may have the opposite effect to that desired.

Parental pressure to eat can also stem from a desire to avoid wasting food that has been prepared, and the belief that children should 'clean their plates'.

However, sometimes the portion sizes that we serve to children are unrealistically large, meaning that it is unrealistic to expect the child to finish the meal and every meal will appear 'unfinished'. In this case, it is not the child eating too little, but the portion size being too large.

Pressure to eat has been linked with a number of negative consequences. These are:

- Less liking for the food

This can be caused by the negative experience of being forced to eat. Children are quick to make associations between foods and unpleasant experiences that accompany them. If a child is pressured to eat more than they wish to, then the negative emotional and/or internal feelings of being too full can become associated with a particular food, leading to a reduction in liking for the food. - Less willingness to eat the food

Similarly, willingness to try a particular food can be reduced if the initial experiences are negative. For example, a child's first exposure to cabbage may be met with refusal, either due to their natural neophobia-based response (see thefood refusalpitfall section) or a lack of hunger. If this refusal was met with constant verbal coaxing and a parent attempting to put the cabbage in their mouth, the association that the child would likely make with cabbage will not be a positive one. - Overeating and overweight

Pressuring a child to eat can undermine their ability to learn appropriate appetite control. Children need to be given the opportunity to learn to recognise their body's hunger and fullness signals. Through experiencing feelings of hunger and a reduction in these feelings when they eat, children learn how their body signals that it requires more energy and, conversely, when enough energy has been consumed and it is appropriate to stop eating.

Although hunger and fullness are internal feelings, research has shown that they can be overridden by a number of factors. Pressure to eat is one way by which children might be urged to eat more than their body requires.

Over time, feelings of fullness lose their significance, as they no longer signal that the meal should stop. Rather, children learn to continue eating, even after they start to feel full, stopping only when their plate is empty, or when their parent says that it is okay to stop.

This means that children listen less to their body and so food intake becomes dictated by factors other than what the body requires. Research has also shown that children eat on average 30% more when offered a larger portion of food.

Offering children portion sizes that are too large and pressuring children to eat more than they desire are important factors in the development of overeating and overweight.

What should I do instead?

Except in very rare cases, children are extremely good at knowing when they are hungry and when they are full. Therefore, it is important to trust them and believe that they will eat if they are hungry. By doing this, you should not feel a need to pressure your child to eat. This is something that they will do willingly if their body requires food. Similarly, children's natural tendencies to reject new or bitter foods should not be met with pressure. Rather, keep offering foods and accept refusal, acknowledging that this is a normal developmental phase and that what you do is important in determining whether this is a positive or negative experience for your child.

Things to try

- Examine the evidence

How long is it since your child last had a snack or filling drink, such as milk? Are they really hungry? Are they too tired to sit at the table and eat well? Is your child unwell and therefore not hungry? Try using a diary to track the number and timings of snacks, drinks, meals, and naps to see if your child's routine could be contributing to their eating behaviour. - Put yourself in their shoes

Try to imagine what it would be like if you were not hungry and you were being coaxed to eat, or even force-fed, or if you were unsure of what it was you were being asked to eat. How would you feel? Empathising with your child and seeing your behaviour through their eyes will help you to recognise that this behaviour is likely to have the opposite effect than you intended. Each time your child refuses food, remember to see things from their point of view. - Step back and be objective

Eating should be a pleasurable experience for your child that meets a biological need. It is not about satisfyingyou. Try to get satisfaction from knowing that your child has eaten as much as they desire and thatthey feel satisfied, rather than from having them eat an amount of food that you have defined. - Trust their tummies

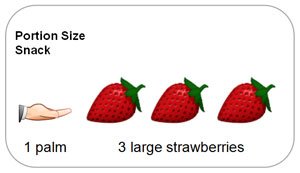

Our bodies are very good at letting us know when we are hungry and full. However, constant interfering - by asking children to eat when they no longer want to - can disrupt this. Eating when hungry and stopping when full is a behaviour that we want to safeguard, not undermine, so try to allow your child to tell you when they are hungry and full. - Check portion sizes.Children's tummies are smaller than adults' and you may be serving too much food and therefore setting unrealistic expectations. As a guide, a single portion of each food is roughly what would fit in the palm of the child's hand. For example, if serving lasagne, give a palm-sized portion of the lasagne and 2-3 palm-sized portions of vegetables. For dessert, try a palm-sized portion of fruit, with a palm-sized serving of natural yogurt. Remember that all children's appetites differ, but sticking to the'palm rule' for each food will help you avoid giving over-sized portions of single foods.

As an example, for a two year old, a palm-sized portion of strawberries would equate to three large strawberries.

(Information about suitable portion sizes for toddlers can be found here.)

Source: https://www.childfeedingguide.co.uk/tips/common-feeding-pitfalls/pressure-eat/